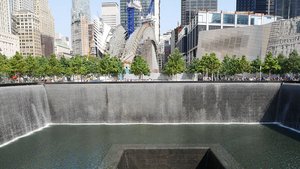

The 'sacred ground' of the World Trade Centre site now houses a museum and twin pools

Nearby, Santiago Calatrava’s spiky transport interchange, bristling with a much denser steel structure than he originally envisaged, is still being built, at the frankly unbelievable estimated cost of $3.44 bn. Disappearing into the sky right behind you is the building once called Liberty Tower in the Daniel Libeskind Ground Zero masterplan; now prosaically 1 World Trade Centre, by David Childs of SOM. It retains Libeskind’s symbolic height of 1776 feet (date of the Declaration of Independence) but otherwise seems to be merely another faceted glass skyscraper, if super-tall. But the crowds haven’t come to see these. They have come to gather around the memorial pools and to visit the new 9/11 Museum. And so have I.

The pools and the museum set between them, along with the associated landscape, together form the National September 11 Memorial and Museum, built on – and in – what is routinely described as ‘sacred ground’. Such exercises are fraught with sensitivities, and the whole exercise has been understandably controversial. Still, there it is. It ‘bears solemn witness’, in the words of the museum’s mission statement. The new commercial buildings going up here step back to allow this place of remembrance to speak.

For me, this was the latest of several return visits since I first saw the site in December 2001, three months after the attacks, when the wreckage was not only a horribly powerful presence in its own right, but even still smoking in places. The trail of debate and competitions since then has finally come down to this: a piece of urban renewal unlike any other.

One response to this unprecedented tragedy would have been to build normal commercial Manhattan back over the site and continue as if nothing had happened, so demonstrating that such acts of destruction are futile – erecting nothing that could inadvertently glorify the atrocity itself. There was a movement simply to rebuild the Twin Towers in exact replica. A memorial could have been placed elsewhere, as London did with its 7/7 memorial. But in Manhattan, unlike London, the act was concentrated in one place, above ground. So the sacred-ground view prevailed, which meant that the marks of the event remain. Landscaped scar tissue, you might call it. A few early first world war cemeteries also show traces of the marks of conflict in this way, as does the shell of the old blitzed Coventry Cathedral next to Spence’s replacement. It’s a valid approach.

You will have seen the photos but it’s not until you are there that the sheer scale of these pools becomes apparent. These footprints bring home the vastness of the old Twin Towers.

The execution of the twin pools, by architect Michael Arad and landscape architect Peter Walker, is well done. These take the form of cascades occupying the footprints of the twin towers, an acre each, the water falling to a lower level and then disappearing via a square void into the earth. The names of the victims in bronze surround the pools at handrail level. You will have seen the photos but it’s not until you are there that the sheer scale of these pools becomes apparent. These footprints bring home the vastness of the old Twin Towers. Look at just one pool; imagine that as a floorplate repeated 110 times; then double it for the two towers with their structural skin and pioneering use of lift-interchange at sky lobbies. The original achievement of architect Minoru Yamasaki and his engineers was prodigious, its destruction proportionately huge.

The glazed above-ground museum building by Snøhetta is reticent, to the extent that it’s easy to overlook entirely in this charged context – the pools draw all your attention. It’s a slightly crumpled form, apparently meant to convey a sense of damage, but your experience of it is fleeting: it might as well be a subway entrance, given that the museum proper (by architects Davis Brody Bond) is subterranean.

It’s a slight shock to find that you have to pay $24 to get into the museum – nearly the same as the Museum of Modern Art. You descend on a ramp deep into the ground, past the rough concrete ‘slurry wall’ of the structural ‘bathtub’ built to hold back the East River from the complex’s foundations. It is an immense subterranean space, and by no means all of it is revealed (Libeskind wanted more). And you get right down to those foundations – like broad steel rails, bolted to the bedrock, from which the columns of the buildings rose – and realise that the rectangular volumes hanging above your head must either be the undersides of the memorial pools or representations of them. Down here at bedrock is also a concrete mausoleum, a repository for unidentified human remains, bearing a 60-foot long text from Virgil’s Aeneid, the letters fashioned from the metal detritus: “No day shall erase you from the memory of time”. This too is controversial: in its original context this phrase was glorifying a massacre, as several classicists have pointed out. It is not the only moment when you find yourself shaking your head at how, inevitably, the aggressors as well as the victims might feel they are being commemorated here.

The space is the true memorial, and the exhibits cannot compete with it – telling though many of them are, especially the buckled metal columns of the destroyed building. You sense that they struggled to fill it all. A crushed fire tender tells one story; an old Honda motorbike beautifully restored by a fireman’s colleagues following his death in the disaster because he had been planning to do this himself, but never got round to it – well, that’s a bit mawkish, though it says much for the people involved. And as for the gift shop with its Twin towers mugs and ties – they’re still trying to strike the right tone there.

One thing, however, remains: a sense of enormous power. Forget the exhibition displays. Down there at bedrock, seeing the ingenuity of the people who built the original WTC, you marvel at their achievement. It was destroyed, at hideous and continuing global human cost, but its revealed remnants, and the solemn cascade pools above, are impressive and moving. We can do things like that. We are a resourceful species. That is a proper memorial and, despite everything, a cause for optimism.