Hans van Heeswijk's insistence that extending The Hague's Mauritshuis gallery of Golden Age art needed a huge subterranean lobby has paid dividends

There’s a certain charm to an art gallery that needed to close its shutters whenever the sun shone into its rooms to protect its impressive collection 17th century Golden Age Dutch art, even if it was somewhat impractical. But the 1644 Mauritshuis in The Hague, home to Vermeer’s famous ‘Girl with a Pearl Earring’, was originally built as a private home. Designed by Renaissance architect Jacob van Campen, it was intended to hold the art collection of the Dutch governor to Brazil, Johan Maurits. Bought by Holland’s government in 1810, it was a state guesthouse before opening as a museum in 1875. Situated on the Hofvijver, the urban lake it shares with the Dutch Parliament, it’s part of a complex of government buildings.

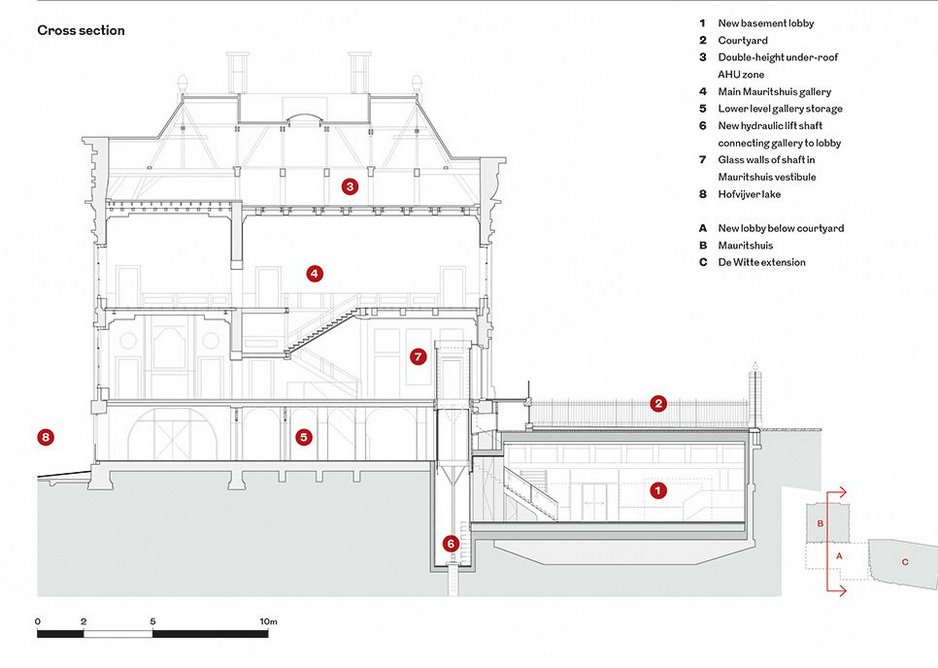

However, the museum found itself ill-equipped to deal with visitor numbers – which were expected to grow to over 300,000 a year – so it was decided to take out a long lease on a 1930s annex to the famous de Witte club on the east side of the Mauritshuis’ courtyard, and to connect to it by building a tunnel back to the basement under the courtyard. However, architect Hans van Heeswijk, winner of the competition to propose how the two buildings might be connected, had bigger ideas. The result is a large subterranean public lobby running under a road to link the two, part of a €30m refurbishment to create a state-of-the-art museum, which opened at the end of June.

This was no mean feat. In much of Holland, ground works involve dealing with a high water table, and this was no exception. The new 900m2 underground lobby extension and the 2400m2 de Witte building doubles the area of the Mauritshuis to 6800m2, providing a new entrance lobby, temporary exhibition, auditorium and offices, shop, café, toilets and cloakroom. Building it required a flexible approach to the foundations and a sensitive upgrade of the existing buildings – both national monuments.

Van Heeswijk was helped by the Mauritshuis having already extended beneath the square in the 1980s, with a cramped two storey extension that provided toilets, café and repository. But he won over the jury with his wish to do away with a floor, open out the space to a double-height volume and connect the building under the road to the de Witte extension, to access temporary exhibition stores, auditorium, café and offices. Van Heeswijk claimed IM Pei’s Louvre as his inspiration, and as was the case there, the logic was as clear as the proposal was unobtrusive, generating a small courtyard with a circular glazed lift and spiral stair on its west side to take visitors to the basement, to then orientate them within the new 60m by 15m space.

A lot of remediation to the existing structure was required. The firm’s proposal involved not only removing a floor that had given lateral stability to the basement, but also pulling the structure away from the west canal-side wall to create the open entrance court. Temporary shuttering was inserted around the perimeter and cast in situ reinforced concrete poured in front of the existing walls, increasing thickness from 500mm to 650mm to cope with ground water pressure on the now unrestrained double height walls. The roof deck – the courtyard floor – was also removed and rebuilt at 1150mm thickness to pin the perimeter retaining walls in place, allowing the creation of a 13m by 4m toughened, laminated glass walk-on rooflight on the east edge of the courtyard, to pull light deep into the lobby. Below the road, solid 800mm square concrete beams running east to west were laid on two transfer beams either side of it. The east beam allowed rooflights to give views west to the de Witte from the lobby, while the west transfers the load of its 1930s façade onto three pairs of 350mm diameter columns, forming the link to its basement. With the de Witte basement level 1500mm higher than the new floor, a secant wall of 1m diameter concrete piles was cast around the perimeter so the floor could be dug out and a new slab cast at the right level. Before this was done, however, the under-road ‘link’ space of 900mm thick slab and 500mm thick retaining walls had to be cast underwater out of waterproof concrete, before the existing courtyard retaining wall and the de Witte basement could be opened up to create a single space.

The structural engineer was so sensitive about subsidence that it temporarily froze the ground around the dig by pumping in liquid nitrogen with pipe needles

But it was perhaps the smallest ground intervention, a new hydraulic lift shaft from the new lobby up into the piano nobile of the Mauritshuis, that was most risky, setting a 2.5m by 2m concrete shaft into its original brick and timber piled foundations. In fact, says van Heeswijk, the structural engineer was so sensitive about subsidence that it temporarily froze the ground around the dig by pumping in liquid nitrogen with pipe needles, allowing soil to be dug out before precast concrete sleeves were craned into place.

Inside, this hydraulic lift is a small wonder. Popping up in the Mauritshuis’ old vestibule, directly in front of the main entrance, it is ingeniously hidden by having the marble floor rise with it when it ascends to the first floor. With the marble set in a steel tray, when the lift runs back to the basement, the tray returns to floor level, leaving no trace of the mechanism save for the vestibule’s new glass wall. This, van Heeswijk explains, means the traditional formal entrance could remain in use for dignitaries (the tempered gallery zone prevented it being used as an general entrance), while continuing to meet access requirements.

Optimising the quality conditioned internal environment and increasing its efficiency was key. Van Heeswijk explains that the strategy was to deal with air handling by treating it as three sections: all high demand handling for the Mauritshuis was to be concentrated where the old kit used to be, in the roof of the gallery, but better performing air handling units were installed and the old service shaft runs reused. Air handling for the de Witte building was similarly sited in its roof, dealing with exhibition spaces, offices and auditorium, and a separate plant room was created at basement level for the less demanding lobby, behind the WC banks. All use high and low level intake and exhaust.

With the de Witte also a national monument, the firm adapted its large public rooms for temporary exhibition and auditorium use without major reconfiguration, insulating them with rigid internally, and better conditioned for their purpose. Its art deco staircase was restored, along with the stained glass rooflight topping off the stairwell, and its 3m high single-glazed openings were replaced using MHB steel triple-glazed frames with a carbon fibre thermal break. Holland’s equivalent of Crittall, they maintain the glazing’s original 1930s fineness, even at scale.

Making the Mauritshuis’ envelope conform to international gallery standards was more complex. Van Heeswijk explains that the building fabric and timber-panelled wall linings of the building were stripped back to their internal brick skins, and timber floors taken up. Within the original timber framework of the interstitial zone, the architect ran rigid insulation to bring the wall up to the necessary performance criteria before the original finishes were re-applied; this reduced the overall room size by about 70mm. The windows were easier: the 17th century facade had 19th century frames and even these were incorrectly specified sashes. The firm specified what look like vertical hinged frames, using triple glazed toughened and laminated glass with a low-e coating, to give thermal and security protection. Though paintings are screened from ultraviolet light, perforate roller blinds have been installed to give them further protection if needed.

It might not now be like having your timber shutters drawn closed by a maid in a Dutch bonnet, but in ensuring the Mauritshuis’ renowned art collection has been housed in a state-of-the-art facility and preserved for the future, its restoration has been (quite literally) groundbreaking.

Credits

Client Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis Foundation

Architect Hans van Heeswijk Architects, Amsterdam

Mauritshuis restoration design Askon

Eden, The Hague

Interior design Stephanie Gieles Interieurontwerp, Delft

Routing Reynoud Homan, Muiderberg

Constructional consultant ABT, Delft

Installation consultant Arup, Amsterdam

Structural consultant DPA Cauberg-Huygen, Den Bosch

Architectural historical research De Fabryck – Bureau voor Gebouwhistorisch Onderzoek, Utrecht

Lighting consultant Hans Wolff & Partners / Lighting Designers, Amsterdam

Building superintendent Hans van Heeswijk Architects and ABT, Delft

Quantity surveyor Basalt bouwadvies, Nieuwegein

Principal building contractor Koninklijke Woudenberg, Ameide

Foundations and fabric contractor Volker Staal en Funderingen, Rotterdam

Suppliers

Installations Kropman Installatietechniek, Rijswijk

Security installations Siemens, The Hague

Lifts Mitsubishi Elevator Europe, Veenendaal

Forecourt lift shaft Octatube, Delft

Interior Van der Plas Meubel & Project, Den Bosch