Robust clay tiling belies the fluid form of Rwanda’s new cricket pavilion which looks like a ball bouncing off to the boundary

The trace of a bouncing cricket ball or the form of the surrounding Rwandan hills – that’s how Light Earth Designs (LED) conceived its latest building, a new cricket pavilion for the Rwanda Cricket Stadium Foundation and the first and only international standard cricket ground in the country. It’s a neat metaphor for the building, which drops in height from 15m to 12m to 8m as it tumbles down its sloping site.

Composed of three parabolic vaulted layered tile shells, the pavilion is in Gahanga, a suburb on the edge of the capital Kigali. To one aspect is the village, to the other are the lush green flood plains of the meandering River Nyabarongo and woodland savanna characteristic of this area near the equator and tropical rainforest belt of Africa.

Light Earth Designs was awarded the commission in 2012 through a connection made by co-founder Tim Hall who spent five years in Rwanda with his partner as part of her work for the Department for International Development. The team had already completed a similar project using tiled parabolic structures for the Mapungubwe Interpretation Centre in South Africa on the borders of Botswana and Zimbabwe. That project positioned the shells in clusters rather than a string, yet was critical in showing this client that LED could mobilise local workers to learn new tile making and laying techniques.

The brief was relatively simple – a pavilion accommodating a restaurant, bar, umpire facilities and kitchens on the edge of a new pitch laid out on virgin land. The foundation has relocated here from a temporary ground in the city which had formerly been associated with the mass genocide of Tutsi people in the 1990s. Rwanda’s difficult recent past forms the backbone of the charity’s very existence to develop cricket in the country, which has no history of the game. The building is part of a drive to encourage healing after all the atrocities. It will also help enable the nation to host international teams, in particular to participate in Commonwealth competitions – for which Rwanda is eligible as one of only two voluntary members, even though it was never a British colony. Yet because the client is a charity, the project had to be stopped at each stage of the design – initial feasibility, planning permission and construction – in order for the client to raise more money for the next phase. This explains why the 650m² project took five years from start to finish.

Light Earth’s design responds to the practical aspects of the brief as well reinforcing it with social responsibilities. While tiled vaulted arches are not a new invention – they have long traditions in Catalonia, France and Italy – LED co-founder Michael Ramage came to them at MIT through his tutors’ teachings on the late 19th century architect Rafael Guastavino’s Tile Arch System in America. Light Earth can be credited with adapting them for use for local material conditions in Africa and discovering site-specific ways of construction by, for example, training local skilled contractors and low skilled workers to build them, as it did here.

The Rwanda Cricket Pavilion uses 65,000 earth pressed (unfired) soil cement tiles of 140mm by 290mm. Light Earth’s goal is to create sustainable, low impact buildings that are adapted to local conditions. Rwanda is a landlocked country so importing materials is expensive. Consequently, earth for the tiles was lifted directly from the ground on site, mixed with 10% cement and hydraulically pressed to form a stable brick, though Ramage explains that a sufficient strength could have been achieved with 5% cement. The bricks were then assembled into the arches in the traditional method – laid from the base upwards using a minimal timber structure as a guide. The first layer comprises tiles joined together using plaster of Paris for its rapid setting time, followed by two to four further layers of tiles, depending on the scale of the arch. These are laid in traditional mortar in overlapping directions – in perimeter rings or diagonal – building up from the sides until they meet at the top. The video above shows the technique in action on previous project for a conference centre in Kent called Pine Calyx.

In between each layer, Light Earth Designs has inserted Tensar TriAx, a geogrid subgrade stabilisation more commonly used in roads, to enhance the stability of the structures in what is a mildly seismic zone. The building’s double curvature also provides better structural rigidity than a single curvature, as seen at a house LED was involved in at Staplehurst, Kent, which featured on Grand Designs in 2008. Whereas that project was planted with a green roof, this one is finished with a crust of fist-sized granite stones – again local to the site – set in mortar, adding weight and stability, and helping the building evoke the geological qualities of the landscape.

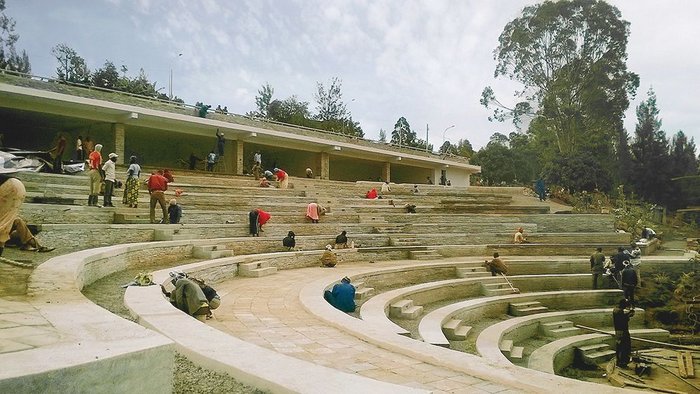

Together the shells provide shelter for the various spectator and sports activities. They are left open to the sides, with the two larger vaults enclosing freestanding table-like structures, the tops of which are used for the bar and restaurant. The undersides of the tiled arches are left naked, while the floors and perforate bond balustrades are constructed using low carbon agro-waste-fired bricks developed by Swiss NGO SKAT Consulting. The pavilions do not contain spectator seating. Instead this has been embedded into a grassy bank surrounding the pavilion along one third of the oval. Visitors can sit either on benching or on the bank itself. The banking creates a wonderful natural amphitheatre with great views to the pitch and wetland valley beyond, and makes it certain that this will become a special place for the sport and the people.